MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

Likir monastery is situated 2 hours west from Leh and my starting point for the easy three day trek.

Assembly hall of Likir monastery.

A few minutes outside of the village, view towards the Zanskar range.

Fox on the way to the first pass.

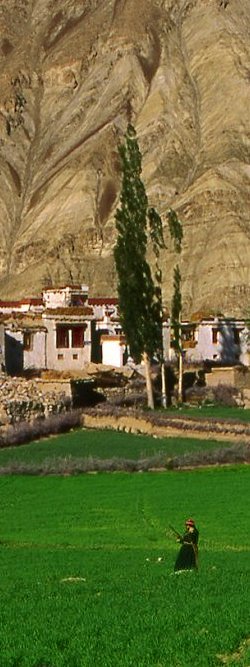

Woman of Sumdo takes a break from working in the barley field.

Yangtang is a pretty village 4 hours after Likir, and a good place to stay for the night.

Barley is the staple diet in Ladakh, and women work in the fields most of the day.

Inside the village, narrow alleys lead to the center where the monastery forms the middle of the small town.

Prayer wheel in front of the monastery.

Courtyard and meeting point, the dozen houses of Yangtang are built .

Likir: Leh - Likir - Yangtang

Leh - Yangtang

Leh Ė Likir Ė Yangtang (Day 3)

I feel well acclimatized and ready for a short trek on my own. Joel (from www.project-himalaya.com) pointed out an easy trek which takes 2-4 days from Likir to Temisgam, also known as Sham trek. It starts a little to the west of Leh in the village of Likir, and crosses several low passes with pretty villages in between.

For a luxurious start I take Wangchukís jeep instead of going by public bus. After leaving the frugal valley behind weíre in the desert where the tarred road is a long straight black line that disappears on the hrorizon. Ochre and red hills give way to blue sky and white puffy clouds. A perfect day to start trekking. For an hour, the snow of the Zanskar range dominates the scenery to the south, occasionally pockets of green appear in the side valleys to the north and indicate habitation. After climbing a little pass the road descents towards the Indus river. The two rivers have distinctive colours: the magic turquoise of the Indus river ends abruptly when it joins the river coming from south. The brown Zanskar river comes from Padum and winds its way through a narrow canyon. The plateau on which weíve travelled since Leh has ended. Green barley fields contrast against the orange rock, white houses dot the colourful fields. The village of Basgo was once the seat of the the Ladakhi kings. Their fortress is still standing Ė though partly in ruins - and looks like a natural extension of the washed out red soundstone pillars. It remains impressive even to today, imagine what it must have felt like for the traders from Kashmir and Srinagar who came scrambling up the valley to see this magnificent display of strength and power.

Three hours after leaving Leh we drive up a little sidevalley to the north, passing the village of Likir on the way to the monastery. It was built in the 11th century, but burned down, and was reconstructed 200 years ago. At the very end of the valley, high above the village, lies the massive compound where construction of a large outdoor statue of Buddha Sakyamuni is almost finished. In the background rises the 6'000 m high snow-covered range that separates the Indus valley from Nubra valley - the 5'350 m high Likir La would take me there but that's not a trek you can do on your own.

The monks are very busy, either working on the statue itself or whitewashing the outer walls, so Iím on my own. The large assembly hall misses some atmosphere, but the large windows and fine paintings on the wall make it a special place. Nevertheless, the visit to the monastery is shorter than I thought.

Itís around noon, Iím ready to start trekking but need lunch. Thereís a simple restaurant in the village. Wangchuk is very insistent that he doesnít want lunch. While Iím waiting for noodle soup, we talk about our families. He was born in Rudok, a trading post in Western Tibet, fled to Ladakh in 1959 and settled in Choglomosar near Leh where many refugees live. His two youngest children go to school there, another one is in Dharamsala and one even in Bangalore in the far south. The highway there impressed him very much, especially the speed it allows.

As a good-bye present, Wangchuk gives me a copy with important Hindu and Urdu words, and a map. I have to promise a few times to inform him when Iím safely back in Leh. Hoping to find a guesthouse to stay in tonight, I set out on a small trail that leaves the village to the west. I admit that it feel strange at first, walking in an unknown region with a just small backpack - I didnít even take a sleeping bag - and just a little food. Once Iím sure Iím on the right trail I start to feel better and enjoy the walk fully. After the village the trail descends to the creek Likir Topka. The white monastery is visible through blossoming bushes and tall poplar trees. Dark clouds gather over the Zanskar range and rain down over there, but on the north side itís fine.

Houses and fields are spread out, and then the gentle climb to the Pobe La pass (3'550 m) begins. Quite abruptly the vegetation ends and a desolate valleys leads up to the pass. Small rivulets must carry water from snow melt or heavy rain, theyíre dried out and only some tiny patches of grass and yellow flowers cover the hillside. Lizards with a flat head hide under rocks, they seem more like geckos than real lizards. Iím pondering how life is possible here when a hissing noise startles me. 40 meters from me a dog-sized animal looks at me - in an aggressive posture. In the few seconds which remind me of a standoff, I realize itís not a wild dog or wolf but a large fox. It has a spiky nose, bushy tail and a red-brown-black white colour fur. After watching me it slowly walks up the hill, turning around every few meters to watch me. Then it disappears over a ridge and walks down a valley.

Some minutes later Iím on the Pobe La which is marked by a small prayer flag. I look down into a completely barren sidevalley. The kinds of lizards living here are much bigger (20 cm), and have a yellow and red neck. It doesnít run as clumsily as the geckos, its speed makes it look as if it doesnít run but takes jumps instead. I reach the bottom of a north-south valley and am surprised because there is no village. I turn right and walk higher up. Between the trees appear two white-washed houses. So this must be the village Sumdo, it is very small but picturesque. The rich vegetation lowers temperatures instantly. The gurgling creek and the shade make it a very tempting place to stay, but Iíve only walked for two hours. What makes the thought even more enticing is a look ahead. A long, hot climb in a narrow gorge is not what Iím looking for.

After Sumdo the trail continues in a canyon. The barren rock is not as boring as it seems, after some time the different colours and structures appear and make it an interesting walk, if it werenít for the heat. Iím very happy when, after an hour, on the trail it seems to flatten out and Iím very curious to look into the other side from top of today's second pass, the 3'650 m high Charatse La. Itís Ladakh at its best: Huge hills with colourful washouts rise in the dark blue sky where dark monsoon clouds travel to the north, desert-like valley at the bottom and between the arid landscape lie green barley fields and a whitewashed, walled village. The contrast is stunning. The colours are fantastic.

Itís another half hour to the school above the town. School is just finishing. The teacher is Norbu, a 26 year-old local from Yangthang. He left his village at the age of 10, and studied many years in the south; going first to Dharamsala and then for further studies in Chennai. He didnít really know what he was in for when he decided to go to Chennai he tells smilingly: Ąmany people donít even speak Hindiď. Now heís back, and enjoys it; though it is a life completely different.

His family still lives in the village, and runs the guesthouse ĄNorbuď. His younger brother, who also happens to be one of his students, brings me down to the village. Women plant seeds of barley in the green fields. I really enjoy village life, and enjoy it. A dozen houses make up the village which has the appearance of a fortress. Houses are built close to each other and form the outer wall. Narrow alleys lead out to the fields. Inside this wall stands the gompa at the center, the old monastery. Whether the layout was chosen for protection from wind and dust, or invaders, or simply to use all the land for agriculture is something I cannot find out.

I am shown my room, a small building on the roof-top with a big window front facing the Zanskar range. Stunning views and comfortable room with some blankets. Down the valley, along the craggy cliffs, the view goes towards the Indus valley where the river must be, and then high up on its other side up the black rock faces into the snow that tops the Zanskar range. Itís cloudy but rain isnít imminent, nevertheless I stay in the house for the rest of the day.

When dusk sets it around 7 oíclock the family calls me for dinner. In the large but not very lavish living room burns a small fire on the open hearth. Norbu, his younger brother, father, mother and grandfather sit around the fire to enjoy a typical Ladakhi dinner. I doubt that there is much variety in food, and different meals are dictated more by supplies in the different seasons than by taste. There is rice (a food relatively new since it does not grow here), lentils, a salty spinach-like vegetable, and chapatis. It is a simple but very tasty meal, and I really enjoy it.

I am fascinated by the grandfather, he is over 80 years old and still in very good health. Norbu translates some questions for me. His grandfather used to be a trader in his younger days, he brought apricots to Lhasa. Since the apricots that grow in todayís Ladakh arenít of the best quality, he went to Baltistan first to get the better kind. Tibetís capital is 2'000 km away, and he travelled there five times.

Trading formed an important aspect of Ladakhi life. Though it was on the southern feeder of the Silk Route, it was not necessarily this long distance trade of goods for the urban elite that affected the normal peasant. And though the geographical location would have enabled the Ladakhis to act as middlemen, it seems that traders from west Kashmir came themselves all the way to trade. But the local subsistence trade did play a huge role for regular Ladakhis. The people in western Ladakh did not own much cattle, but had vegetables, fruit and corn to offer to the nomads who roamed on the high pastures to the east. They moved on the wind-swept plateau, enduring hot dusty summer and icy winters, living from what their animals, mainly yaks and goats, offered. Most valuable was the wool, out of which the famous pashmina was made, and over which wars were fought. Both parties had something the other didnít, and the trade of apricots, barley, and potatoes for meet, cheese, wool and salt was necessary for both.

However, for some more enterprising individuals like Norbuís grandfather, this barter trade for everyday things was not enough and they participated in a difficult but lucrative long distance trade with Yarkand in the north, or Lhasa to the east. Trading with Tibetís capital was an important economic factor of Ladakh until the 1950s when the Chinese occupation put the century-old tradition to a halt. It is ironic that even though Ąglobalizationď is seen as a todayís progress, the real achievement happened hundreds of years ago when adventurous men went out looking for routes and passes to venture into unknown territory, for the sake of profit and probably not a small portion of adventure. In fact this traditions were stopped by modern humankind, in form of borders, large scale wars (locals conflicts were widespread back then), and modern inventions. Not to romanticize the trade days too much, once the railtracks were laid in the 1940s, some traders didnít walk the old route to Lhasa any longer, and took the train from Manali to Siliguri in the very east of India instead and then from there by horse to Lhasa.

So in many areas humankind didnít progress, quite on the contrary. Thoughts like these and imaginations about the old manís adventures on his trade journeys accompany me into a sound sleep.

|

Summary Part 2:

After two days in Leh I am acclimatized enough to do a little trek on my own. Starting in the village of Likir, it's a four-hour trek in a scenery of stark contrasts. Arid valleys and gullies lead to two low passes. Cultivated areas stand out in the desert. From the second pass I look into the valley of Yangtang. A large area is covered by bright green barley fields, at the bottom lies the village of a dozen whitewashed houses. |