MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

Dendi and Bagman, two of our Sherpas.

Without porters - their smiles and carrying capabilities - trekking would only be half as much fun.

The strength of Trisuli porters is legendary, the women carry a little less than the men, but still much, much, much more than I could

Carpet weaver in typical Tibetan dress in Phale, a settlement of refugees.

Farmers in Ghunsa plough the fields for planting potatoes.

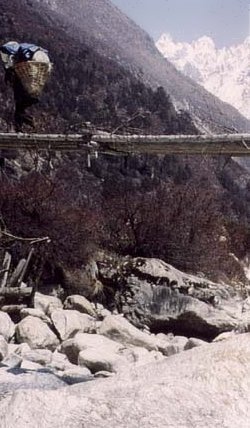

Bridge over the Ghunsa Khola halfway between Ghunsa and Kangbachen.

We stare in awe. Jannu, 7'710 meters high wall of rock.

One the 'smaller' companions of Jannu.

Our camp in Kangbachen, small dots far down in the valley.

Kangchenjunga: Sekathum - Ghunsa - Kangbachen

Sekathum - Ghunsa - Kangbachen

Sekathum - Amjilosa (Day 5)

Shortly before morning tea, a cock's crow wakes me at 600. It is a fine morning once again, warm at the valley floor but there's snow at the end of the valley, behind the ridge towers a big summit. A trail goes up the precipitous valley wall and then disappears behind a curve. Joel wants us to walk together because the exposure is severe and there are some crucial junctions. I slow down at first but then pass the others to get warm and stop for breaks more often than usual. The trail is narrow, straight drops go down to the river far down in the valley. It reminds me a little of southern France where the water runs in constants rapids between boulders in narrow gorges, the steep wall covered by bushes and trees.

Of course some people of our group went ahead and missed the junction. Since no Sherpa is there to run after them we all have to follow 'their' route, instead of climbing up and haveinglunch near a waterfall we stay close to the Ghunsa Khola, cross it first and then follow it on the other side. It is another rough climb on a narrow slippery trail. A tremendous waterfall end in big sprays before reaching the bottom. Colorful trees and red bushes add to the nice views that reward the extra-effort and little detour. And when I see the lunch spot I am not unhappy that we went this way.

The river has formed a shallow pool half an hour further up, it is an enchanting place: rocks form a large swimming pool with turquoise water, overhung by trees, a shallow but slippery entrance invites for a swim. It is colder than the previous day in the river and I'm in the water only the very five seconds it takes for a good picture. My stomach finally got used to Nepali spices and kitchen hygiene and I fully enjoy a triple portion of lunch.

On the map today's walk looked like a gentle stroll along the river, and then a little climb to camp. The endless ups and downs before lunch were a little tiring, but when we get a little farther ahead and see the place for tonight, some sighs can be heard.

High above us on the opposite valley wall is a solitary cluster of three houses: Amjilosa. After crossing on an iron bridge it is a tough climb up, the river gets smaller but the houses don't seem any closer. Once again it surprising to see how far you can walk in a short time, and in the middle of the afternoon we reach the three houses where we will put up camp. The term 'we will put up camp' is slightly misleading; usually it is our crew who does it while the tourists (with a few noble exceptions) literally stand around and complain when the tent-entrance faces the 'wrong' way. I spend moost of the time with the crew and the few cool tourists.

It'd be interesting to learn about the villages we pass, but I couldn't find any literature on them. This town's name could mean 'The Place of the Doctor in the South', but again it is speculation. The people who live her are clearly of Tibetan origin and follow Tibetan New Year's ritual. A sure sign of getting into high country.

Rain starts a bit earlier; the porter carrying my bag just as the downpour starts. It also gets chilly after sunset, the mix of cold, wetness and mud is uncomfortable: time to retreat to the sleeping bag with a good book, a hot drink and Swiss chocolate. It's tempting to hibernate in my tent, but then soup and popcorn lure us to the mess tent.

Amjilosa - Gyabla (Day 6)

It must have been really cold last night; snow has fallen far down and lies like a fine powder on the surrounding hills. It is a nice contrast to the dense fir forest and the high yellow grass we walk through. And the sky is cloudless again. The forest is changing its face, instead of lush broad-leafed trees it becomes less dense and the leaves on the rhododendrons are still small.

After the first climb the valley bends and more snowy hills appear. They are pretty low and not part of the Kangchenjunga range, but nevertheless it is a taste of what's to come. We climb up to pass the precipitous hillside below and get into small patches of forest. Then it's a gradual descend towards the river. More trees grow along its bank, but the valley is too steep for agriculture on a large scale and thus the population is small. In Thyangyam we stop for awhile, allowing the kitchen crew to catch up. The lunch spot is not as close as promised by Joel, which is fine with me. Every minute of more ups and downs will increase my appetite and make the lunch taste even better than normal. A clearing in the forest next to a waterfall is a pleasant spot for rest, well worth the longer walk in the morning. The porters have eaten their dal baht somewhere on the way and overtake us while we wait for our much-needed calories. I wouldn't mind eating rice and lentils every day, in fact I would enjoy it, but most tourists are sick of it after the third time so we get more varied food.

After dal baht we continue in the pleasant forest along the Ghunsa Khola. While climbing up the last big steps in a gully prayerflags fluttering in the wind above us, a minute later we reach a green plateau. A few wooden houses are surrounded by wheat fields, more buildings are on a second plateau higher up. The main village is built on an elevation above, but instead of exploring this afternoon I help put up the tents and engage in a fun game of Frisbee with our crew.

The views are getting more alpine, big snow-capped mountains rise into the cloudy sky high above a waterfall. It was a beautiful day until late afternoon, again we have rain at late night but it is not as chilly as the previous evening and everybody is in a good mood.

Gyabla - Ghunsa (Day 7)

It took longer than usual but now I am finally in 'trekking shape'. This includes not only physical fitness, probably more important is the ability to enjoy every step and all the different sights, sounds and smells. And I am in the mood for side-trips.

I was told that the 'real' village lies on the plateau higher up so I leave early after breakfast and climb the little hill. Wheat was planted recently and the offshoot covers most of the gentle slope. A dozen wooden houses with shingled roofs stand far away from each other, most of them are (temporarily?) deserted. This does not make the solitary walk less enjoyable, the views down the valley are nice. After a tough climb through rosehips bushes on steep goat trails I join the main trail before it crosses a small creek and soon catch up with the others in the forest. Huge pine trees covered by moss and fern dominate the scenery, giving the trees the impression of ancient giants guarding the valley. Landslides from higher up have ripped through the forest, but now everything is stable and we get ahead quickly. After following the rapids for most of the morning, a little climb takes us to an open pasture.

If a final indication of my trekking-mood was needed, here it comes: appetite. I'm very hungry and envy the porters who are cooking their dal baht 'on the trail', two hours later we reach some houses and stop there for our lunch. The prospect of a filling meal cannot suppress a feeling of disappointment: I thought we have lunch in Phale, one of the largest Tibetan villages in the area. And now that we are here the village is not interesting nor is anybody else there. The houses seem shabby and the fields are not looked after.

Luckily this was not Phale, just a little 'suburb'. Twenty minutes later prayerflags on a big boulder announce the large settlement. The monastery overlooks the settlement that lies on a clearing, bordered by forested valley walls. The courtyard in front of the wooden gompa is the meeting place of the upper part of the village. A few women and some monks sit in the sun and chat. The women wear the traditional dress: a simple chuba with an apron and a large silver belt. The monks are from the Gelugpa sect and wear red robes over yellow shirts. The two novices are not knowledgeable, one of the older monks puts aside a beautiful orange piece of cloth with Buddhist symbols, unlocks the door that was hidden behind it and shows me in the Walung monastery. It is a relatively well-lit room and without the usual strong smell of butter lamps. A lot of statues and paintings are put on the altar or hang at the ceiling. Some of it looks quite old, but except for a nice statue of Chenrezi (Avalokiteshvara) and some thangkas the artifacts don't seem to have a large artistic value. The community is too small to support an affluent gompa.

The group we quickly met in Suketar has arrived and a rumor will have it that they dislike us because of the offending clothing of some of us. I cannot blame them for feeling that way. But they are not very respectful either when they enter the monastery with shoes and hats. I stay there for some time and play and chat with the kids. The rest of the group has left for Ghunsa, another big village three hours further up the valley where we will stay for two days. I try to hurry to escape the clouds that have built up at the end of the valley.

While passing a construction site in the village I meet a woman who carries a big log. I offer to help. Five logs and fifteen minutes later I really have to say good-bye. Hopefully I will have some time on the way down to spend a day here. So far these encounters were rare and I really start to miss them.

A small creek forms the town's end, just afterwards is the school building. School is finished and most children have already left, the few who are still there are more amused than impressed when I read from their Tibetan schoolbooks. Two teachers are still there, one of them speaks English. The school is partly financed by the Nepal and the Tibetan government-in-exile. I am surprised to hear that the Nepalese government supports schools where local culture is learned. In addition to that Nepal increasingly clamps down on Tibetan activities in order to please its big donor China. Westerners who have their own school projects have told me that one positive effect of the Maoists is that schools are forced to changes they long resisted, like accepting children from low-caste families or teaching local language and customs.

The clouds have nearly caught up with me and I have to leave early again. In retrospect the walk from Phale to Ghunsa is the most idyllic one during the whole trek: after passing a water-driven prayerwheel and a natural threefold chorten covered by moss, a lovely forest begins. The variety of trees and bushes is immense, it is not dense and patches of grass grow between the big boulders. Yellow and green moss is the dominant color in the dense forest that grows along the river. Bridges cross the many waterfalls and small creeks that come from the steep valley wall.

I start running to escape a possible downpour, so despite my long stops in Phale I overtake most of our group just as Ghunsa comes in sight. After a bend in the river I see the village on the other side. A wooden bridge decorated with colorful prayerflags takes me over the river and I enter the village where I quickly find our cook Mege who went ahead. Then it starts to drizzle very lightly - I made it just in time.

Ghunsa consists of three dozen wooden buildings that are distributed evenly on a level clearing. The houses are built in clusters, stone-paved trails connect them. The main road disppears in a lovely forest of firs and pines to the north, on one side snow-covered mountains and lofty pinnacles of rock tower over the village that is bordered by the river. All houses share the same architecture: wooden cottages with a large balcony, stable beneath, and a roof covered by wooden shingles and stones, and two small firs with prayerflags to ward off evil spirits. People own the house they live in, some of their fields are adjacent to their house, others are further away.

According to the name, people live in the village only during winter (ghun -winter; sah - place), but nobody has moved higher up yet.

The campsite is not very big and might turn muddy soon. Since we stay here for two nights for acclimatization it worth looking for a nice lodge. Tourist infrastructure is not as developed as in other areas of Nepal, but there are some lodges to choose from and it does not take me long to find a good room. The few tourists we meet have just come down from Kangbachen and are dissappointed: snow fell every day for a week - not in huge amounts but enough to cause serious discomfort for the porters. To prevent a potential mutiny they decided to turn around and will try tomorrow to cross another pass to the east.

Ghunsa lies at 3'500 m where temperatures are considerably colder, especially after sunset. Instead of putting up the mess tent we stay in the lodge, the last frozen toes are warmed up by the soup.

Ghunsa - Rest Day (Day 8)

I was afraid it'd be terribly cold in my large chamber, but the newspaper on the wall keeps most of the cold wind out. I enjoy a cozy night and wake up at sunrise with sound of talking from the living room below. First I scratch the ice from the inside of the window and see the American group crawling out of their frost-covered tents. The sky is dark blue, some mountains are in the orange rays of the rising sun. It is cold but very dry and thus not uncomfortable. At 700 I walk over to our camp just in time for breakfast tea.

All the locals got up quite awhile ago and are already at work. Kids carry yak dung from the stables to the fields. They throw it on several piles that are scattered over the field and return to get the next load. The smaller kids help and play on the fields, the older ones are probably in school.

Since the coming days will offer great mountain scenes, strenuous day hikes are not advisable and I stroll around the village instead. The regular trail to Ghunsa along the river misses the chorten that is built further up overlooking the valley. For some reason this is a very solemn place, very quiet, surrounded by small juniper bushes that rustle in the cool breeze. The paintings on the ceiling must have been renewed some time ago, the color and clay on the outside is crumbling, but this does not take away the charm of the old monument. Faded prayerflags flatter on the long poles. Maybe because of rockfall a new chorten was built on the other side of the river. Falling rocks also threaten the old monastery, named Tashi Chuding, nearby. The main hall is built on a large boulder, the fading red color indicating that it is not in regular use anymore. But the newly put up prayerflags and the lock on the door indicate that it still has significance although not the same as in earlier times. A hundred years ago it used to be a Nyingmapa monastery with over 80 monks and some nuns, the monks lived near the monastery, the nuns in the village. Back then also the village was much larger.

Only one old monk is in the village to take care of things, like the monks in Phale he is from the Gelugpa tradition. It is one of the four main Buddhist schools and was founded by a famous reformist monk (Tsongkapa) who introduced stricter rules than the other sects: alcohol and marriage are not allowed. Seeing Ghunsa's Lama drink chang in the morning is clearly against the rules, but then again it must very difficult to live a monk's life when you live in a community of laymen, and I don't know how respected he is among the villagers. His 'colleagues' in Phale certainly don't have too high of an opinion of him, I will find out on the hike out.

A women with her two children work on the field below the monastery, a picturesque scene with the gompa and precipitous mountains rising high in the background.

Back in the village I try to make myself useful and help planting potatoes. Jokingly I am offered to walk in front of the two yaks with the plow, I accept hoping that the guy does not mean it seriously. Luckily he was just kidding; guiding the moody animals without being stabbed by the horns requires some experiences. After a minute of throwing potatoes into small holes I am relegated to minor tasks. I carry shit around, literally. The baskets are heavier than they appear, after a few loads I give up.

Eric wanted to send postcards and somebody pointed to a building saying it is the post office. He gave the family sitting on the veranda the cards and a hundred rupees for stamps. The looks on their faces must have been puzzled; they are probably wondering why they get postcards and money as a gift from a stranger.

They invite me for the traditional Ghunsa afternoon snack: boiled potatoes with salt and chilies. It is a welcome snack, and entertaining for the locals who watch me clumsily peeling potatoes. A big pile of uncooked potatoes is sorted out into the ones worth keeping for meals and the smaller one that are good for planting. These are cut into pieces and will be planted the next morning. While working, the (grand?)mother is watching a small baby and tries to fix me up with her 20-year old (grand?)child. My declines are met with many smiles and much laughter.

Just across our campsite is the house of the lodge owner's own house. A ladder goes to a large veranda from where a small door takes you to the dark living room. It is also the kitchen and bedroom, nevertheless it is a 'public' room and visitors are welcome. I sit near the fire, watch the flames and listen to the conversations. Sometimes I manage to catch a few words.

The housewife is in control and sits at the left of the fire, the oldest daughter across her on the right. I'm sure quite some Ph.D.-papers were written on the subject of 'Sitting positions in Sherpa culture', but I have never been able to find one. Anyway, one does not need to be a careful observer to find out that it is a delicate matter and that the best seats are reserved for family and relatives. Seeing tourists taking the best ('warmest') seat and stretch their feet to the fire makes me cringe inside. When unsure or not specially invited sitting further away is a good idea. Humbleness is seen as a virtue. Cups are a similarly coded custom, ama-la (literally 'mother') has a beautiful cup with a fine silver lid.

It is hard to tell who is the head of the house. The husband does not seem to drink and usually gets food last. His wife drinks a little bit of Tongba from a beautiful jug with silver ornaments.

I give myself a treat and take a hot shower at the campsite. A pipe goes from the owner's living room over the road to the small bathhouse. I indulge with a clean conscience since the big water-barrel is placed on top of the fire and no extra wood was wasted to boil the water.

The Spanish group that arrived camps out near 'my' hotel. It's a family trip, the 60-year-old has visited Nepal almost 20 times and now for the first time goes trekking with his two sons. They have a good time, though he has problems with his knees and stays here for three days while his sons go up to Kangbachen. Afterwards they will meet in Ghunsa and together cross the pass to the east.

Ghunsa - Kangbachen (Day 9)

Yesterday the loads were divided up and after handing out additional clothes to porters we are ready after breakfast. It getting distinctively colder at altitudes above 3'500 meters, especially at night. It was really cold at night again, I noticed it when I got out once for the regular pee- stop but then decided to avoid the cold and the watchdog by using a flowerpot.

Porters are tough and strong, but they suffer in cold like everybody else and their eyes hurt the same as ours when they get snow-blind. Therefore every tourist should make sure that his or her porters are well equipped. Some agencies do not outfit 'their' porters at all, because they are hired on the fly and agencies do not want to pay for their gear. The International Porters Protection Group (IPPG) has a clothing-bank in Kathmandu where clothes can be rented. Joel brought lots of clothes from IPPG, the male porters really like their new outfits. The Trisuli female porters look more skeptical and do not want to wear anything else than their traditional clothes. Hopefully they will change their mind when they really need warm clothes.

People are up early and continue their work on the fields. Nobody is ploughing yet, probably because the frozen ground makes it more strenuous than at noon. Kids and older women carry fertilizer from the stables under the house to the fields. I am early and help them carry a few baskets. It is hard work and I am not using to carry 25 kg on my back with a string over my head. Even the 10-year-old children have a basket of a substantial size. If I did this work for half a day I'd probably be unable to move for a week.

Most Tibetan people (except Khampas) are smaller than Europeans, and this cannot be explained genetically (children of Tibetan families born in Switzerland are as tall as everybody else). So it might come from the fact that they carry heavy loads while growing up, or due to a less nutritious diet.

We leave the village in company of our porters who are in a great mood; maybe the beautiful morning uplifted their spirits as much as it did mine. The weather is brilliant, and rather cold; blue sky, crisp air, hoarse-frost on the ground. The ice melts away fast when the sun hits the ground as we reach the forest. The valley is walled in between rock faces on the left and steep high snow-covered mountains on the right. The wide Ghunsa Khola runs in the middle, a lovely forest with larches and pines grows between the river and the glaciers. The rivulets coming from the mountain range are tiny compared to the gorge in which they now run. Landslides are another indication that at some time of the year - probably monsoon - the valley changes from 'peaceful' to 'very active'.

We take a break on a cleared plateau and enjoy the views to the north: a peak resembling a needle dominates the range near Kangbachen. The glaciers on the right tower high up, icicles cling to the steep rock faces on the left. A great morning!

A traditional wooden bridge crosses the torrent near our lunch-spot at Rampuk Kharka. We go slowly and stop often, some because of altitude, some because of the great scenery. The trees and bushes are getting less dense, the valley opens up and I wonder what views we'll get in the afternoon.

The traverse over a potentially unstable landslide area requires full attention for a few minutes, but then there is time to sit down and let yourself be overwhelmed by the views:

A wide glacier flows in a bed with gentle curves, a massive wall of ice and snow towers over everthing, vertical rock faces reach high into the sky. The two summits in the foreground are very impressive, nevertheless they are still topped by Jannu. Not only is it 7'710 meters high, in addition it is almost completely vertical. When you follow the ridge and think you see its summit, you have to look further up to the little head that sits on top of the broad shoulder. The 'smallest' of the precipitous mountains next to it looks like Eiger North face, Jannu's face is at least twice that high. I sit down in awe of the stupendous peaks, taking in the scenery in small bits. Words fail to describe the view and the feelings it evokes.

Half an hour ago we were sweating on the ascent, now a cold wind requires windproof clothes. Glaciers have formed the landscape around us, the area is more level and small trails zig-zag through the boulders. Adjacent to big rocks are a few little shacks of yak herders who will move up here from Ghunsa during summer, right now they are abandoned. The village of Kangbachen comes unexpected, as we stand on a little hill we see a dozen buildings at the confluence of three valleys.

After crossing a small creek we are in the village and wait near a little bridge. Most snow has melted but there is enough left for a snowballfight with the Sherpas and kitchen crew who arrive shortly after us.

Ram Kaji could convinced a farmer from Ghunsa to come up with us to open his lodge. It is a simple building with one room for our kitchen, a dining-hall and three sleeping quarters. In last Manaslu's group there might have been some discussions (and hard feelings) about who gets which room, this group is more relaxed in this respect. After years of trekking and sharing tents, the single tent that is standard when trekking with Jamie and Joel is a luxury. But I'm also happy with a room and since nobody wants it, it's mine for the next two days. That's worth re-decorating: after ten minutes things are arranged neatly and the room looks cozy; I have a nice bookshelf, clothing line, found some old nails on a roof which make perfect coat hooks, and got two candles from Mege.

Joel has spent some time in kitchen this evening: the outcome is a delicious chilli tomato sauce.

|

Summary Part 2:

We follow the Tamur river upstream, after crossing endless sidevalleys on suspension bridges the scenery starts to change. The valleys become more narrow, ascents are steeper and the dense forests change their appearance. Firs and cedar take the place of large ferns and broad-leafed trees. Chortens and prayerflags announce the first settlement of Tibetans, Phale. Just after Ghunsa, the largest town in the area, alpine scenery begings. Moraines and mountains dominate the landscape; hanging glaciers cling to steep rockfaces and glint in the sun. In Kangbachen the stupendous face of Jannu towers over us, a sheer wall of rock rising high into the sky. |